MaverickFM

Pathfinder Games

This week, we invited guest writer, Kruger, to discuss at military tactics. Kruger is currently serving in the military and has had a life long interest in all things to do with warfare.

A few years ago I started looking into how the modern infantryman fights a battle. I was very much into playing modern war simulators - first person shooters and real-time strategy games - and war movies. My obsessive side had taken hold and I needed to investigate until I had the true nature of the fire fight. The first incongruity that I noticed was while watching amateur footage of firefights in Iraq and Afghanistan - for one there was a lot less, 'Charge!', no one shot while on the run and mostly it was difficult to even see where the opposing men were shooting from. These were the first among several differences that became apparent.

I believe that to understand what differentiates the modern infantry platoon from the formations of the early-modern period armies of Napoleon and his contemporaries we need to look at what fundamentally changed to affect how an infantryman fought his enemy. From a general consensus this was the advent of the machine gun. This weapon is considered to have been the main cause of the trench warfare stalemate on the Western Front of the First World War. The rate of fire and the rapid development of tactics that created overlapping fields of fire led to a situation in which the massed infantry charges of earlier wars rarely achieved their objectives and always with terrible losses. The machine gun was the inciting event that forced the armies of both sides to experiment with new tactics.

Instead of launching an artillery barrage followed by a massed charge across no-man’s land, smaller units of grenade, machine-pistol and light machinegun armed soldiers would sneak close to the enemy and concentrate to breach the lines, clearing the way for follow on units to consolidate the gains and leapfrog into a follow up attack. By the outbreak of the Second World War, all the major powers had developed a new manual of infantry tactics which we now know as the doctrine of ‘Fire and Manoeuvre’.

This new tactical doctrine was built around the machine gun and focused on smaller formations with more responsibility placed on junior leaders for tactical decisions. I have often heard the maxim that the machine gun, or the squad automatic weapon, is the real weapon of an infantry section and the riflemen are there to protect it; that the modern assault rifle is less an offensive weapon and more of an arm for personal defense. This has to do with the machine gun’s usually greater range and ability to sustain a high rate of fire over a relatively long period of time. That is not to say that in a firefight it is only the machine gunner who shoots, but that the responsibility for the ‘Fire’ goes to the machine gun team, while the ‘Manoeuvre’ goes to the remainder of the section.

In principle, when the enemy is found and engaged the machine gun team immediately starts shooting at the enemy, creating something of a wall of lead. The aim here is not necessarily to kill the enemy but to suppress them - to keep them from shooting back. This is achieved by gaining fire superiority: shooting more bullets more quickly so that the other guy is too worried about getting shot than shooting back. Once the race for fire superiority is won, the ‘Manoeuvre' element makes an assault under the cover of the machine gun team and physically clears the enemy out of their position.

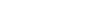

An easy theory to follow, but what does fire and manoeuvre actually look like? To show this I will look at it from an infantry section level, though I have seen the same tactics scaled to a platoon and even a company level. While the exact details and organisation vary from army to army and across wars a typical section consists of between seven and ten soldiers divided into two teams by function and weapons with a section leader and at least one adjoint.

One of the teams carries the section's machine gun, a man portable weapon with a high rate of fire and a range of at least 800 metres, though most can fire effectively out to more than 1000 metres. The weapon is usually served by a two man team, though in recent times single man systems have been deployed (for example the Belgian Minimi/M249 SAW). The German army of the Second World War built their sections around the MG34 and later the MG42, the Americans around their BAR and M1919 and the British around the Bren gun.

The second team is usually armed with the standard service rifle (in the Second World War these were often bolt-action rifles or, in the case of the US forces, semi-automatic rifles and carbines) as well as grenades and, in modern armies, disposable anti-armour munitions.

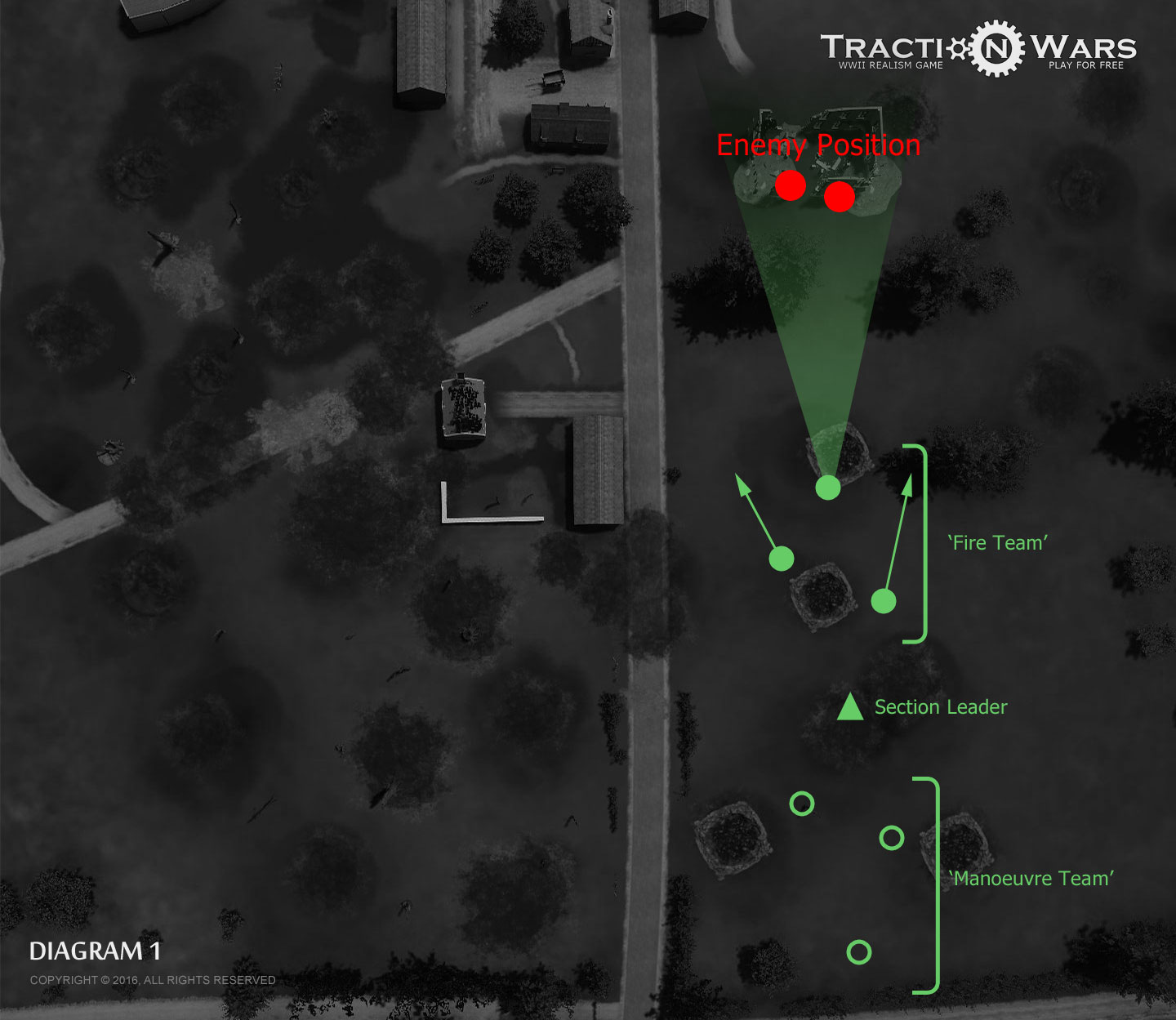

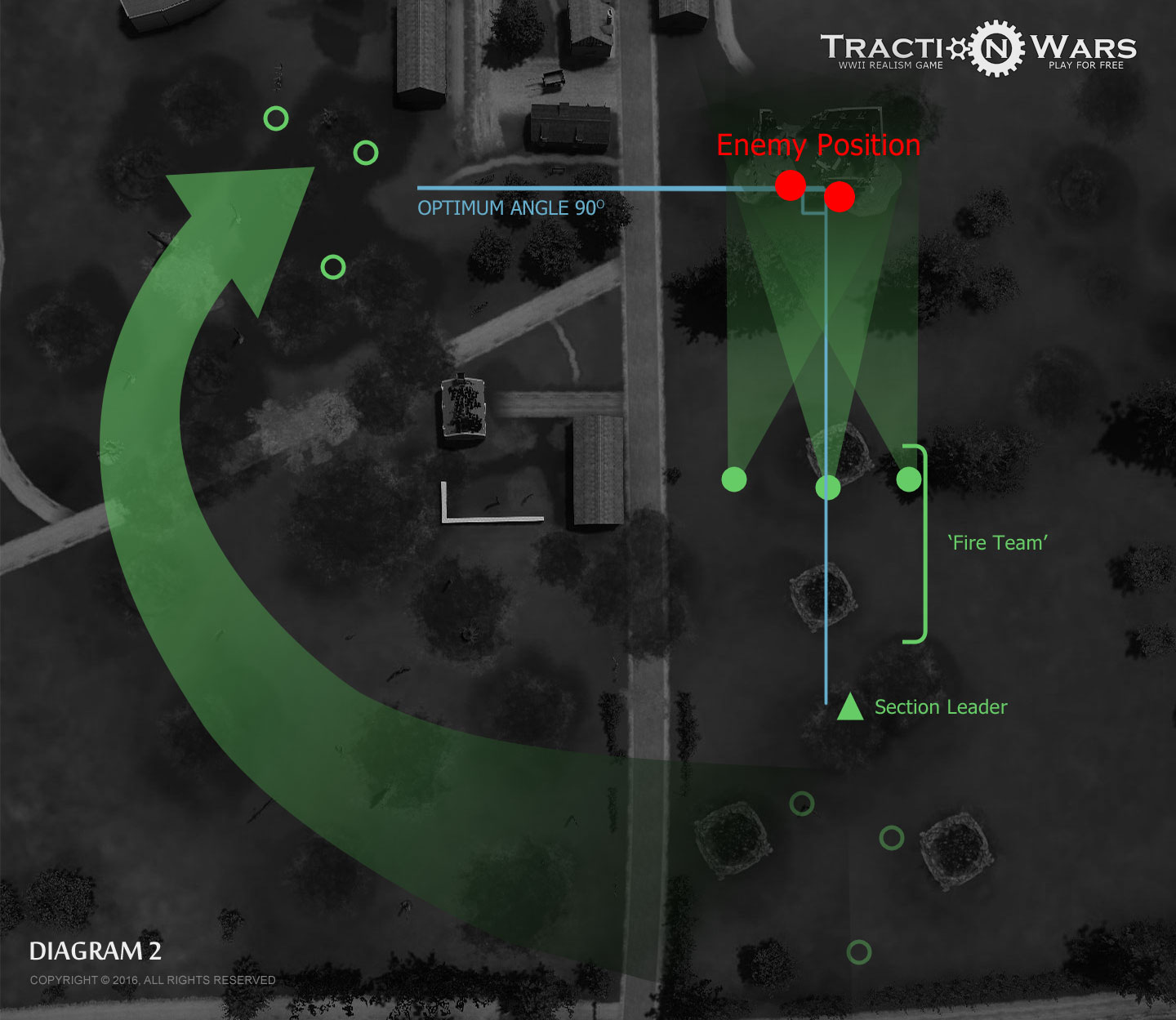

When a section finds the enemy, they immediately follow the react to contact drill which is all about ducking for cover while getting suppressive fire on the enemy. The machine gun is brought on line as quickly as possible and the gun crew attempt to gain fire superiority. The assistant gunner and any other riflemen attached to the machine gun team also fire at the enemy position. The section leader will then decide whether to break contact or assault the enemy position. Assuming that the leader decides to attack he will order his Manoeuvre team to flank the enemy position. The direction of the flanking attack is chosen by the terrain based on speed and cover - another maxim: the terrain commands.Once the Manoeuvre team is in place, at a prearranged signal the Fire team intensifies their fire to better cover the Manoeuvre team's advance across the final open space between them and the enemy. The Manoeuvre team crosses the ground to the enemy position as quickly as possible while shooting. At another pre-arranged signal the Fire team shifts their fire away from the Manoeuvre team to the opposite side of the objective (i.e. if the Manoeuvre team is flanking from the left then the Fire team shifts fire to the right), calls for the Fire team to cease fire before passing through the enemy position. They move weapons away from dead or dying enemies and halt on the far side of the objective in a formation that secures 360 degrees.

The Fire team moves up, passes through the enemy position a second time making a more thorough sweep for prisoners, weapons and intelligence before setting up on the far side of the enemy position. At this stage the section forms a rough L shape on the far sides of the enemy position. Finally, the section rallies and sets up for their next objective.

At a platoon level this plays out similarly except that instead of having a team for each role, an entire section would be used as the base of fire while another entire section would be used to manoeuvre onto the flank and make the assault. A third section should be placed as a cover against the enemy making a flanking attack or reinforcing.

Next time, we continue with how real life tactics might work within a gaming environment.

A few years ago I started looking into how the modern infantryman fights a battle. I was very much into playing modern war simulators - first person shooters and real-time strategy games - and war movies. My obsessive side had taken hold and I needed to investigate until I had the true nature of the fire fight. The first incongruity that I noticed was while watching amateur footage of firefights in Iraq and Afghanistan - for one there was a lot less, 'Charge!', no one shot while on the run and mostly it was difficult to even see where the opposing men were shooting from. These were the first among several differences that became apparent.

I believe that to understand what differentiates the modern infantry platoon from the formations of the early-modern period armies of Napoleon and his contemporaries we need to look at what fundamentally changed to affect how an infantryman fought his enemy. From a general consensus this was the advent of the machine gun. This weapon is considered to have been the main cause of the trench warfare stalemate on the Western Front of the First World War. The rate of fire and the rapid development of tactics that created overlapping fields of fire led to a situation in which the massed infantry charges of earlier wars rarely achieved their objectives and always with terrible losses. The machine gun was the inciting event that forced the armies of both sides to experiment with new tactics.

Instead of launching an artillery barrage followed by a massed charge across no-man’s land, smaller units of grenade, machine-pistol and light machinegun armed soldiers would sneak close to the enemy and concentrate to breach the lines, clearing the way for follow on units to consolidate the gains and leapfrog into a follow up attack. By the outbreak of the Second World War, all the major powers had developed a new manual of infantry tactics which we now know as the doctrine of ‘Fire and Manoeuvre’.

This new tactical doctrine was built around the machine gun and focused on smaller formations with more responsibility placed on junior leaders for tactical decisions. I have often heard the maxim that the machine gun, or the squad automatic weapon, is the real weapon of an infantry section and the riflemen are there to protect it; that the modern assault rifle is less an offensive weapon and more of an arm for personal defense. This has to do with the machine gun’s usually greater range and ability to sustain a high rate of fire over a relatively long period of time. That is not to say that in a firefight it is only the machine gunner who shoots, but that the responsibility for the ‘Fire’ goes to the machine gun team, while the ‘Manoeuvre’ goes to the remainder of the section.

In principle, when the enemy is found and engaged the machine gun team immediately starts shooting at the enemy, creating something of a wall of lead. The aim here is not necessarily to kill the enemy but to suppress them - to keep them from shooting back. This is achieved by gaining fire superiority: shooting more bullets more quickly so that the other guy is too worried about getting shot than shooting back. Once the race for fire superiority is won, the ‘Manoeuvre' element makes an assault under the cover of the machine gun team and physically clears the enemy out of their position.

An easy theory to follow, but what does fire and manoeuvre actually look like? To show this I will look at it from an infantry section level, though I have seen the same tactics scaled to a platoon and even a company level. While the exact details and organisation vary from army to army and across wars a typical section consists of between seven and ten soldiers divided into two teams by function and weapons with a section leader and at least one adjoint.

One of the teams carries the section's machine gun, a man portable weapon with a high rate of fire and a range of at least 800 metres, though most can fire effectively out to more than 1000 metres. The weapon is usually served by a two man team, though in recent times single man systems have been deployed (for example the Belgian Minimi/M249 SAW). The German army of the Second World War built their sections around the MG34 and later the MG42, the Americans around their BAR and M1919 and the British around the Bren gun.

The second team is usually armed with the standard service rifle (in the Second World War these were often bolt-action rifles or, in the case of the US forces, semi-automatic rifles and carbines) as well as grenades and, in modern armies, disposable anti-armour munitions.

When a section finds the enemy, they immediately follow the react to contact drill which is all about ducking for cover while getting suppressive fire on the enemy. The machine gun is brought on line as quickly as possible and the gun crew attempt to gain fire superiority. The assistant gunner and any other riflemen attached to the machine gun team also fire at the enemy position. The section leader will then decide whether to break contact or assault the enemy position. Assuming that the leader decides to attack he will order his Manoeuvre team to flank the enemy position. The direction of the flanking attack is chosen by the terrain based on speed and cover - another maxim: the terrain commands.Once the Manoeuvre team is in place, at a prearranged signal the Fire team intensifies their fire to better cover the Manoeuvre team's advance across the final open space between them and the enemy. The Manoeuvre team crosses the ground to the enemy position as quickly as possible while shooting. At another pre-arranged signal the Fire team shifts their fire away from the Manoeuvre team to the opposite side of the objective (i.e. if the Manoeuvre team is flanking from the left then the Fire team shifts fire to the right), calls for the Fire team to cease fire before passing through the enemy position. They move weapons away from dead or dying enemies and halt on the far side of the objective in a formation that secures 360 degrees.

The Fire team moves up, passes through the enemy position a second time making a more thorough sweep for prisoners, weapons and intelligence before setting up on the far side of the enemy position. At this stage the section forms a rough L shape on the far sides of the enemy position. Finally, the section rallies and sets up for their next objective.

At a platoon level this plays out similarly except that instead of having a team for each role, an entire section would be used as the base of fire while another entire section would be used to manoeuvre onto the flank and make the assault. A third section should be placed as a cover against the enemy making a flanking attack or reinforcing.

Next time, we continue with how real life tactics might work within a gaming environment.

Last edited by a moderator: